Why we drive on the left

A tourist to one of the more chaotic sun-blest nations remarked to his host about the highly random observance of road rules, lane discipline in particular. His host was puzzled “I don’t understand” he said, “We have a very clear rule. In some countries they drive on the left. In some countries they drive on the right. Here, we drive in the shade.”

But why do some countries drive on the left and some on the right?

The origins and reasons are, to some extent, lost in the mists of time but we know that the Romans drove on the left.

Historians have studied a track into an old Roman quarry at Blunsdon Ridge in England. The track was only used for bringing stone from the quarry to a major Roman temple being built on the nearby ridge (near Swindon), and then fell out of use, so it is very well preserved. And since the carts went in empty and came out laden with stone, the ruts on one side of the road are much deeper than they are on the other. From this the conclusion is that Romans drove on the left. There is other evidence of this in other parts of the Roman Empire, and the Romans were great ones for standardising and organising things, so most likely driving on the left applied everywhere in the Roman Empire.

Seven hundred years ago, everybody drove on the left. In the Middle Ages you kept to the left for the simple reason that you never knew who you’d meet on the road in those days and you wanted to make sure that a stranger passed on the right so you could go for your sword in case he proved unfriendly. This custom was given official sanction in 1300 A.D., when Pope Boniface VIII invented the modern science of traffic control by declaring that pilgrims headed to Rome should keep left.

The papal system prevailed until the late 1700s, when teamsters in the United States and France began hauling farm products in big wagons pulled by several pairs of horses lined up in rows. These wagons had no driver’s seat; instead the driver or drivers sat on the left horse of a pair (the Postilion position), often only the rear left horse, so he could keep his right arm free to lash the team and also to ease mounting which is usually from the horse’s left. You can still see the Postilion position in use on the large teams of horses used to pull ceremonial gun carriages etc.

Since you were sitting on the left, naturally you wanted everybody to pass on your left so you could look down and make sure you kept clear of the other wagon’s wheels or overhanging load. Ergo, you kept to the right side of the road. If there was no driver on the front row the lead horses were trusted to make sure you did not veer off the road and down a bank or whatever.

In small-is-beautiful England, though, they didn’t use monster wagons that required the driver to ride a horse; instead the driver sat on a seat mounted on the wagon. What’s more, he usually sat on the right side of the seat so the whip wouldn’t hang up on the load behind him when he flogged the horses – most people being right handed or at least whipping right handed.

So the English continued to drive on the left. Keeping left first entered English law in 1756, with the enactment of an ordinance governing traffic on the London Bridge, and ultimately became the rule throughout the British Empire and remains so throughout much of what is now called the Commonwealth.

The first known keep-right law in the United States was enacted in Pennsylvania in 1792 when they adopted legislation to establish a turnpike from Lancaster to Philadelphia (a toll road, so named as a pike – or long thrusting spear – was positioned across the road and “turned”, or rotated up, when the toll was paid to allow passage. If the traveller tried to slip through without paying the toll the pike was used to attack the traveller). The charter legislation provided that travel would be on the right hand side of the turnpike. In the ensuing years many states and Canadian provinces followed suit. New York, in 1804, became the first State to prescribe right hand travel on all public highways. By the Civil War, right hand travel was followed in every State. Drivers of smaller vehicles with a single central horse tended to sit on the right so they could ensure their buggy, wagon, or other vehicle didn’t run into a roadside ditch and to facilitate easy assistance to alighting passengers behind them – especially those who paid!

When inventors began building “automobiles”, or “ horseless carriages” as they were often called, in the 1890’s, they built them as motorized wagons. As a result, many early cars had the steering mechanism from a horse drawn cart and used a rudder (or tiller) or a rope, but not a wheel, in the centre position where the side of the road didn’t make any difference.

However, with the marvellous invention of the steering wheel (at that time the best thing since the wheel) in 1898, a central location was no longer desirable. Car makers usually copied existing horse drawn practice and placed the driver on the curbside. Thus, most American cars produced before 1912 were made with right-side driver seating, although intended for right-side driving. Such vehicles remained in common use until the mid 1910s. The 1908 Model T was initially built in RHD but in about 1912 Ford switched to a left-side driving position to make it easier for ladies to get into the front passenger seat, as had become the fashion.

The Model T had become so popular (accounting for almost half of all cars on the road) that the rest of the automakers followed Ford’s lead.

In France, before the revolution, the aristocracy travelled quickly on the left, forcing the peasantry over to the right. (There are other theories attributed to one of the Kings Louis being left handed and forcing all to ride/march on the right so as not to be disadvantaged).

After the revolution, in order to blend in, aristocrats joined the peasants on the right. A keep right rule was introduced in Paris in 1794. Later Napoleon enforced the keep-right rule in all countries occupied by his armies (principally the Low Countries, Switzerland, Germany, Italy, Poland and Spain), and the custom endured long after his empire was destroyed.

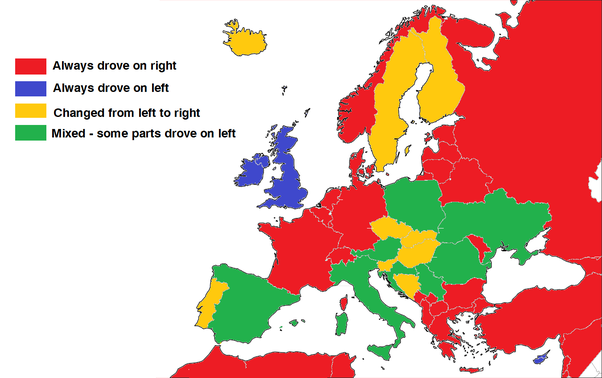

The states that had resisted Napoleon kept broadly left – Britain, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and Portugal. Although left-driving Sweden ceded Finland to right-driving Russia after the Finnish War (1808-1809), Swedish law – including traffic regulations – remained valid in Finland for another 50 years. It wasn’t until 1858 that an Imperial Russian decree made Finland swap sides.

The break up of the Austro-Hungarian Empire caused no change; Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and Hungary continued to drive on the left. Austria itself was something of a mixed case. Half the country drove on the left and half on the right. The dividing line was exactly down the line of Napoleon’s conquests in 1805. Napoleon gave the Tyrol, the Western province of Austria, to Bavaria but it continued to keep to the right whilst the majority of Austrians drove on the left.

When Germany annexed Austria in 1938, it brutally suppressed the latter’s keep-left rules, and much the same happened in Czechoslovakia in 1939.

This European division, between the left- and right-hand nations remained fixed until after the First World War.

In the 1850’s Gunboat diplomacy forced the Japanese to open their ports to the British and Sir Rutherford Alcock, who was Queen Victoria’s man in the Japanese court persuaded them to adopt the keep left rule. Some countries later occupied by Japan also drove on the left.

Korea, a former Japanese colony, switch from left to right driving when the Japanese moved out after WW2 under the influence of the USA and Russia. Pakistan considered changing to the right in the 1960s, but ultimately decided not to do it. The main argument against the shift was that camel trains often drove through the night while their drivers were dozing. The difficulty in teaching old camels new tricks was decisive in forcing Pakistan to reject the change. And Sweden changed to driving on the right in 1963 in direct opposition to a referendum which had overwhelmingly rejected such a move.

I think the reasons for driving in the shade need no explanation.

Main sources “Cecil Adams, “Return of the Straight Dope” (New York: Ballantine Books, 1994), “Ways of the World”, Max Lay Rutgers University Press and US DOT “On The Right Side of the Road” by Richard F. Weingroff